Some proofs of existence provide explicit examples. For instance, a proof of a composite Fermat number is as simple as noting that  . On the other hand, some existence proofs are highly non-constructive, and do not provide explicit examples. The proof that the reals can be well ordered cannot be realised as a constructive proof, since the statement is independent of the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms.

. On the other hand, some existence proofs are highly non-constructive, and do not provide explicit examples. The proof that the reals can be well ordered cannot be realised as a constructive proof, since the statement is independent of the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms.

In this post, we’ll consider the borderline between constructive and non-constructive proofs. I have provided four examples, which vary in terms of constructiveness.

Gardens of Eden

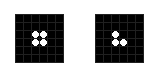

A pattern in Conway’s Game of Life is known as a Garden of Eden if it cannot arise within the successor of another pattern. The proof of the existence of Gardens of Eden relies on the non-injectivity of the rules; two patterns (such as those below) are mapped to the same pattern (namely the one on the left):

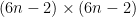

Now, consider a general  pattern. There are

pattern. There are  possible patterns of this size, but at most A =

possible patterns of this size, but at most A =  are non-equivalent. The total number of patterns in a

are non-equivalent. The total number of patterns in a  box is B =

box is B =  . As every

. As every  box determines a

box determines a  box in the following generation, at most A patterns in a box of side length

box in the following generation, at most A patterns in a box of side length  are actually constructible.

are actually constructible.

If we choose n sufficiently large so as to ensure that A < B, then there must exist a Garden of Eden. By writing down the inequality and manipulating it, one can deduce an upper bound of 6859110463024 for the side length of the minimal Garden of Eden. One ‘explicit example’ is the lexicographically first Garden of Eden of this size. A more explicit example is the concatenation of all  patterns of this size, which must itself be a Garden of Eden by virtue of containing one.

patterns of this size, which must itself be a Garden of Eden by virtue of containing one.

Of course, this argument is pretty pointless as a completely explicit example, which inhabits a  box, has already been found.

box, has already been found.

Primes with one billion digits

There’s currently a substantial prize offered by the Electronic Frontier Foundation to discover a prime with one billion decimal digits. Due to Bertrand’s postulate, we can be sure that such a prime exists; it is located between  and

and  . Hence, we can provide an ‘explicit’ example of a prime with one billion digits, namely the largest prime factor of

. Hence, we can provide an ‘explicit’ example of a prime with one billion digits, namely the largest prime factor of  . However, this seems to be ‘cheating’, and would obviously not win the EFF prize.

. However, this seems to be ‘cheating’, and would obviously not win the EFF prize.

Primitive roots modulo infinitely many primes

An integer n is described as a primitive root modulo p if every number in  can be expressed as some power of n. For instance, 3 is a primitive root modulo 7, whereas 2 is not. Dr Roger Heath-Brown demonstrated that at most two non-square integers are not primitive roots modulo infinitely many primes. Nevertheless, no numbers have yet been proved to be primitive roots modulo infinitely many primes. So, we know that at least one integer in the set {2, 3, 5} is a primitive root modulo infinitely many primes, and we can take ‘the smallest one satisfying this property’ to be our ‘explicit example’.

can be expressed as some power of n. For instance, 3 is a primitive root modulo 7, whereas 2 is not. Dr Roger Heath-Brown demonstrated that at most two non-square integers are not primitive roots modulo infinitely many primes. Nevertheless, no numbers have yet been proved to be primitive roots modulo infinitely many primes. So, we know that at least one integer in the set {2, 3, 5} is a primitive root modulo infinitely many primes, and we can take ‘the smallest one satisfying this property’ to be our ‘explicit example’.

Obstruction sets for toroidal graphs

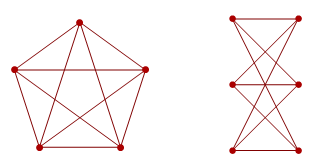

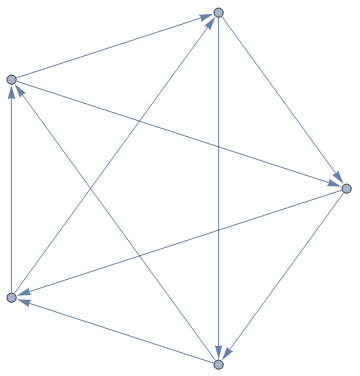

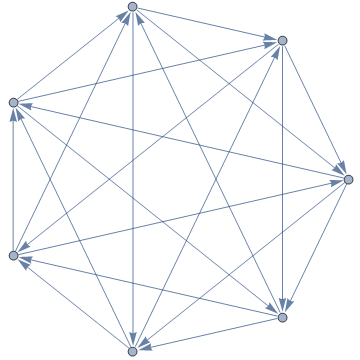

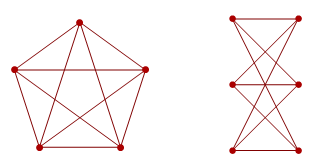

Wagner’s theorem states that a graph is non-planar if and only if it contains either the complete graph K5 or the bipartite graph K3,3 as a graph minor. The Robertson-Seymour theorem implies that we can find a similar obstruction set for toroidal graphs (graphs that can be drawn on a torus without edges crossing), but we have no idea how large such a set could be.

It’s possible, however, to inject the finite sets of graphs into the positive integers. I’ll leave this as an exercise to the reader; it’s not too difficult. Consequently, out of all valid obstruction sets for toroidal graphs, we can choose the one corresponding to the smallest integer. This is still an explicit example in some sense, but even less so than the other examples I’ve provided (there are no size bounds).

If you’ve been affected by any of the issues in this article, please discuss them here in the ‘comments’ section at the foot of the page. In particular, I would like to hear your views on where you draw the line between explicit examples and non-constructive proofs.

as a quartic surface bounding a doughnut, or obtained by identifying opposite edges of a square. An intermediate between these constructions is the Clifford torus, which is the Cartesian product of two circles.