Dating the discovery of the integers is difficult indeed. Positive integers have been used since time immemorial for counting, and positive rationals were later used by the Ancient Greeks to express lengths. However, this was not sufficient, as the Pythagorean theorem shows that the diagonal of a unit square is irrational. Someone was even drowned for proving this! Is he really to blame for the existence of irrational numbers? Anyway, we need a larger field of numbers, the reals, to account for this.

John Conway developed a much larger ordered field, encompassing Cantor’s infinite ordinals as well. We’ll explore this idea in the environment of combinatorial game theory. Lots of games can be associated with surreal numbers; one of the simplest is the game of Hackenbush mentioned in a book by Conway, Guy and Berlekamp.

Rules

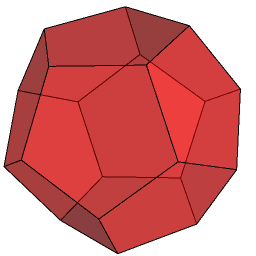

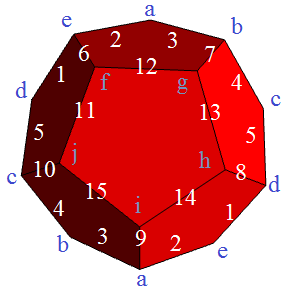

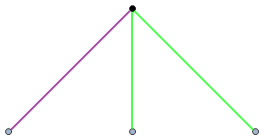

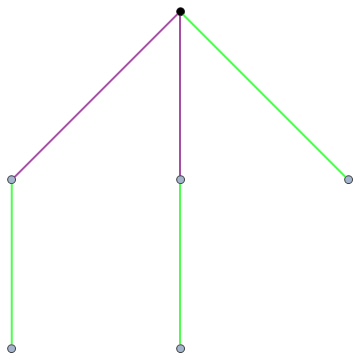

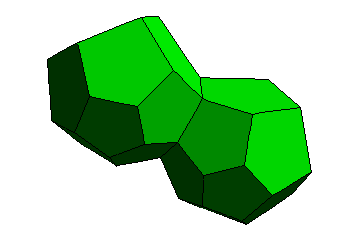

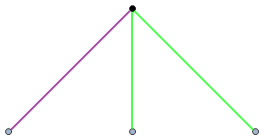

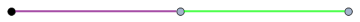

The state of the game is represented by a tree, the edges of which are either violet or green. One vertex of the tree is identified as the ‘root’ (coloured black in these examples). For instance, the following is a valid position in Hackenbush:

Alice and Bob have opted out of being used as example names on Complex Projective 4-Space, so I’ll instead have to resort to using names of people who particularly enjoy the site.

- Vishal and Gabriel alternate turns removing edges: Vishal can only remove violet edges, whereas Gabriel can only remove green edges.

- Some parts of the graph may end up ‘cut off’ from the root in the process. Rather like pruned branches of a plant, they immediately die and disappear.

- This process continues. A player loses when he or she has no valid move.

Evaluating games

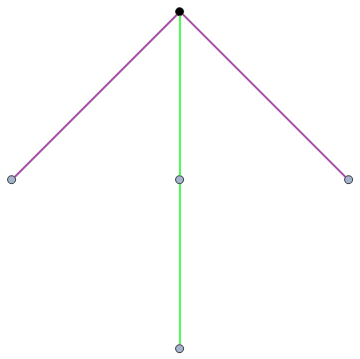

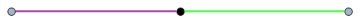

A game is described as positive if Gabriel can force a win, negative if Vishal can force a win, or zero if the person who goes first loses. Clearly, in this instance, it is a win for Gabriel, so the game is positive. Indeed, this game is associated with the number +1. Another equivalent game is shown below, also with a value of +1:

In order to calculate the values of various games, we’ll use some axioms:

- If two games a and b are welded together at the root vertex to form a third game, it has value a + b.

- If all colours are inverted in a game c, we obtain the game −c.

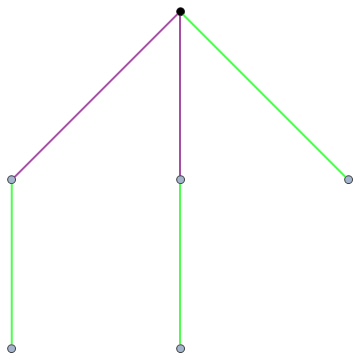

By axiom 2, the following game has value -1:

Vishal obviously wins irrespective of who goes first, as he can remove the violet edge, so this is indeed a negative game. We can add the previous two games together by fusing them at the roots to form a zero game, where the second player has a winning strategy:

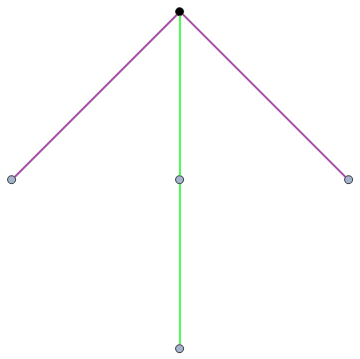

So far, the games have been reasonably simple, as we have only considered star graphs (where the root is connected to all other vertices). What about the following game? What is its value?

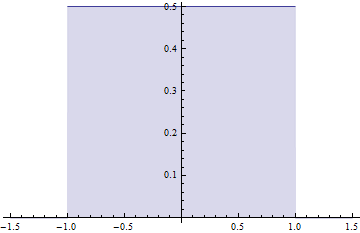

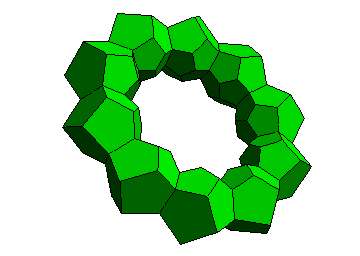

Vishal and Gabriel each have two edges to remove, and neither of them can force their opponents’ edges to disappear. So, this game must again have value zero. By subtracting the violet edges, we obtain a game of value +2. This generalises in the obvious way; for instance, this game has value +4:

More complicated games include the one below. We don’t know what its value is yet, so we’ll call it x.

This must be negative, as Vishal wins. It looks more positive than -1, though, since Gabriel still has a green edge he can remove. We can deduce the value of x by using our axioms. Consider the following tree:

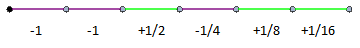

Try playing this with a friend. You should find that, no matter which colour you are, the second player wins. So, this game has value 0, and we can deduce that 2x + 1 = 0. In other words, the original game has value -1/2. We can access any dyadic rational using a finite string, such as -25/16:

Bigger trees than Sequoia sempervirens

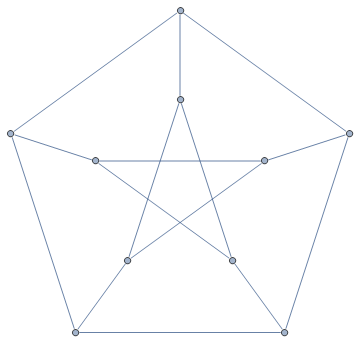

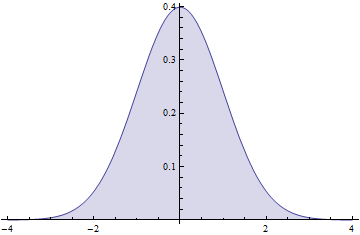

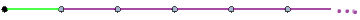

By allowing infinite trees, further numbers can be accessed. We can obtain any real number, for example, by utilising its binary expansion. We can also obtain the infinite ordinal ω (a green string of infinite length), and the infinitesimal ε (shown below).

We can go further by using Cantor’s infinite ordinals to express positions of vertices, and create even bigger infinities and infinitesimals. For instance, we can have a generalised string with value 2ω:

We can verify that this is indeed the case, as Vishal would need two infinite rooted strings of violet edges to restore this to a balanced (zero) game. We can get things that aren’t even ordinals in the traditional sense, such as the game ω − 1:

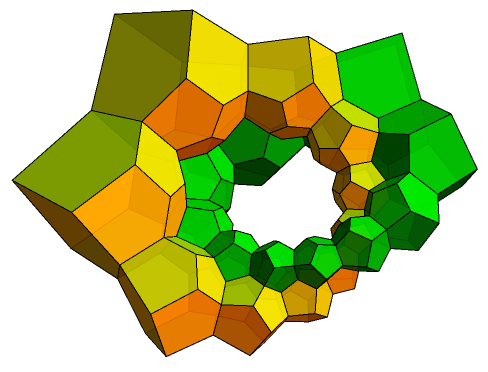

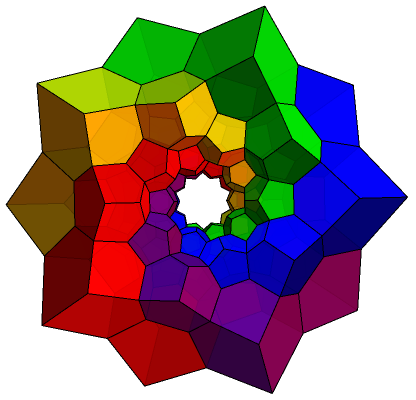

This effectively constructs the tree of Conway’s surreal numbers. Going down-left on the tree corresponds to appending a violet edge to the end of a string, whereas going down-right corresponds to appending a green edge. Lukas Lansky drew this tree for the Wikipedia article on surreal numbers:

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Surreal_number_tree.svg&page=1

Arithmetic with (generalised) surreals

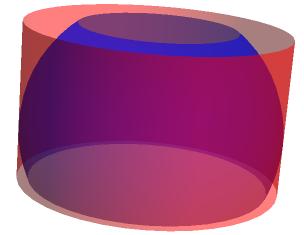

Surreal numbers can be recursively added, subtracted, multiplied and divided, just like real numbers. We say they form an (ordered) field. Indeed, they constitute the absolute largest possible ordered field.

If you were under the impression that this is completely crazy, things are going to get a lot worse. The surcomplex numbers are of the form a + ib, where a and b are surreal numbers and i is the imaginary unit. Like the complex numbers, they are algebraically complete: any polynomial equation in the surcomplexes can be solved.

As the Cayley-Dickson construction depends only on defining addition and multiplication, we can obtain surquaternions (non-commutative!), suroctonions (non-associative!) and, worst of all, sursedenions. I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a generalisation of this blog with infinite posts, namely Surcomplex Projective 4-Space!