Suppose we have a particularly ravenous cat (Felis sylvestris) chasing some particularly tasty mice (Mus musculus, if I remember correctly) across the vast expanse of the real Eculidean plane R². The most interesting case is when mice and cats move at the same maximum speed, so we’ll assume this henceforth. In particular, we’ll discretise time to simplify the analysis.

The most fun way to consider this is to embed it in a game.

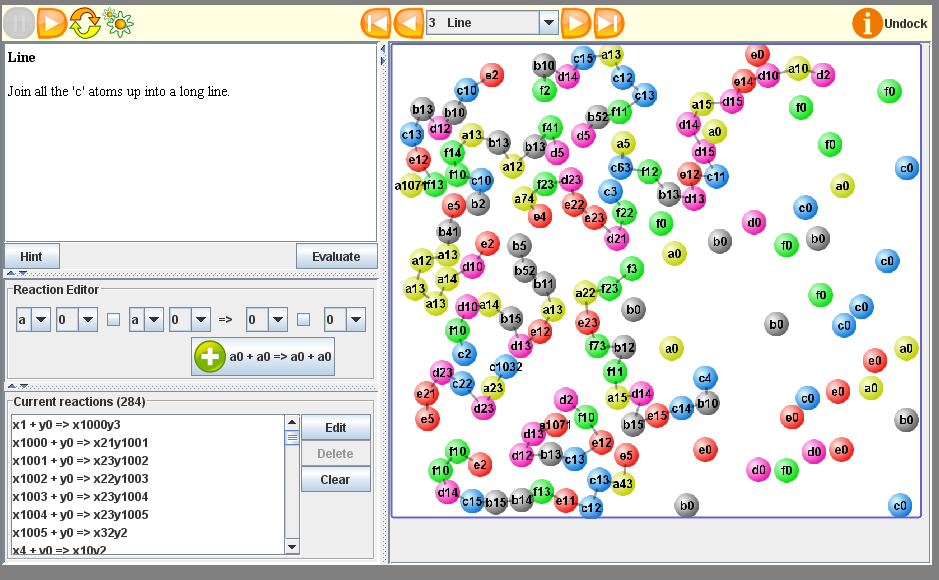

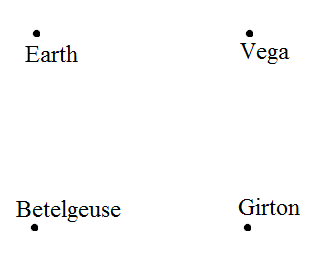

- Given two positive integers c and m, the ‘mouse owner’ decides some initial configuration of c cats and m mice on the Euclidean plane.

- The mouse owner and cat owner alternate taking turns to choose one of their respective animals and move it anywhere within the closed disc of radius 1 centred on its current position.

- If a cat lands on top of a mouse, the cat owner wins. If there is no time for which this occurs, it is considered to be a win for the mouse owner.

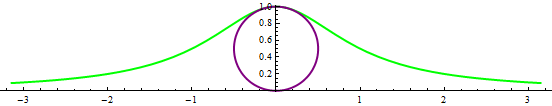

So, for what values of c and m do the mice have a winning strategy? During one Anglo-Hungarian camp, a bunch* of us demonstrated that mice can force a win whenever c = 1, irrespective of the value of m. You may want to prove it yourself. Geoff Smith extended this to the c = 2 case.

*Being a mathematician, I’m only allowed to use ‘group’ to refer to an associative algebraic structure endowed with inverses and an identity.

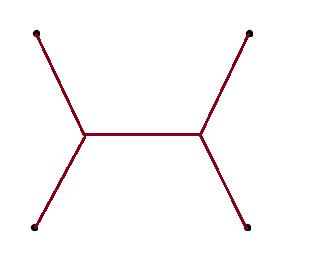

The case for m = 2 is also a win for the mice irrespective of the value of c:

If the abscissa (horizontal coordinate) of a cat moves to the left, then the left mouse moves left. Otherwise, the right mouse moves right. This leads to a winning strategy for the mice.

On the hyperbolic plane, this generalises to a winning strategy for the mice for all ordered pairs (m,c). For the Euclidean plane, however, it is much harder.

If we allow more types of animals, this can be made into a fair, playable game. For instance, you could have a three-player game involving animals isomorphic to ‘rock, paper, scissors’, trapped inside a bounded arena.

Lion and man of indeterminate religion

A variant of this problem is where time is continuous, but the speed is bounded below 1. It was originally phrased with a lion chasing a man (whose religion, due to reasons of political correctness, is left unspecified in academic papers) around a circular amphitheatre. It turns out that the man has a winning strategy (hint: the sum of the reciprocals of the squares converges to π²/6, but the sum of the reciprocals of the integers diverges).

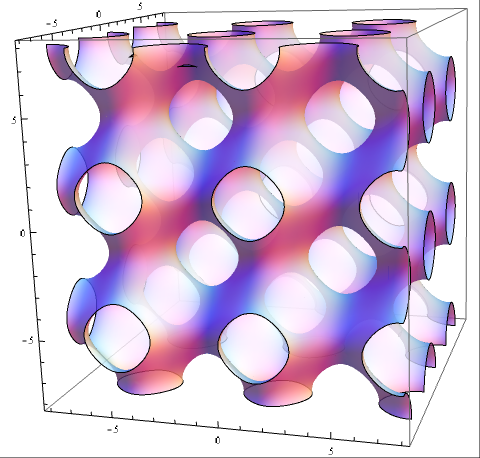

With different spaces and distance metrics, things become more interesting. For example, consider R³ with the norm d² = max(x²+y²,z²), where a ball (set of points within a given radius of a point) is a cylinder. The arena itself is a ball/cylinder, by analogy with the original problem. Bela Bollobas, Imre Leader and Mark Walters contemplated this, and showed that paradoxically both the lion and man have a winning strategy.

A completely unrelated note

I donated blood today, with Tom Rychlik doing likewise for the sole purpose of preventing me from assuming the moral high ground. I told him that 11 minutes was the time to beat, and he wagered five Yorkies against a mention on cp4space that he could manage it in less time. Remarkably, rather like the counter-intuitive lion versus man problem, both competitors ‘won’ in some sense: Rychlik took a mere 7 minutes, but passed out and had to stop after an incomplete donation of 420ml. Consequently, you’re reading this whilst I get to indulge in some chocolate!

Continuing the tenuous links with cats and wagers, I just this moment received a ransom note from Ben Elliott:

“I have your cat. Unless you compute Ramsey(6,6) by 0000 UTC tomorrow, it will be placed in a box. After this point it will be both alive and dead.”

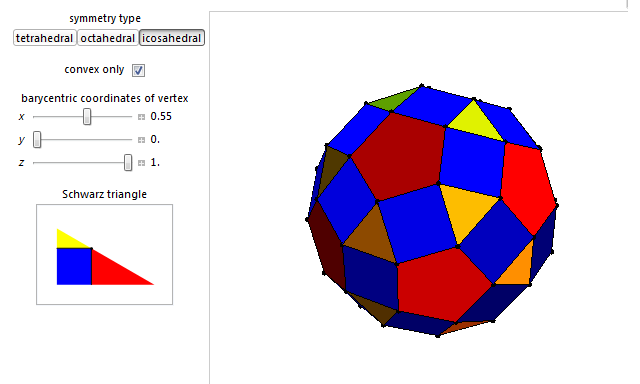

Considering that I am neither Erwin Schrödinger nor in possession of a cat, I’m intrigued to see what will happen. I imagine that he’s referring to the number of vertices n required for there to be guaranteed a monochromatic K6 subgraph within any colouring of the complete graph Kn with two colours. Upper bounds are established and proved in the third chapter of MODA, but they’re far from optimal.