Shortly after publishing my third cipher, the second one (labyrinth) was solved by someone called Patrick. Gabriel had worked out the basis for solving the cipher ages ago, but didn’t actually do the necessary combination of brute-force frequency analysis to decipher it. I’m pleased that no-one cheated by using my Golly-compatible cellular automaton (which, I now suppose, you can run on the iPad implementation of Golly).

I don’t usually entertain requests, but since I had such a great time last night I’m willing to make an exception. Ben and Vishal asked for the next post to involve Markov music and underwater basket-weaving, respectively. My attempt to splice these two very disparate threads (no pun intended) forms the basis of this article.

Penney’s game

This is completely unrelated to the Cantabrigian tradition of dropping low denominations of British money into opponents’ beverages (it happened to me!), but is instead named after its creator, Lord Walter Penney. To relieve the monotony of their early retirement from the world of cryptography, Alice and Bob decide to play the following game:

- Alice selects some three-digit binary sequence of coin tosses, such as HHT.

- Bob follows by choosing a different three-digit binary sequence, such as THH.

- A coin is tossed repeatedly to generate a binary sequence. I’m going to actually do this now, forsaking the opportunity to make a pun on the name of the game and instead tossing a £2 coin bearing an excerpt from a quotation by Sir Isaac Newton. The resulting sequence was THTHH, whence the game terminated as Bob’s string appeared. Hence, Bob won that particular game.

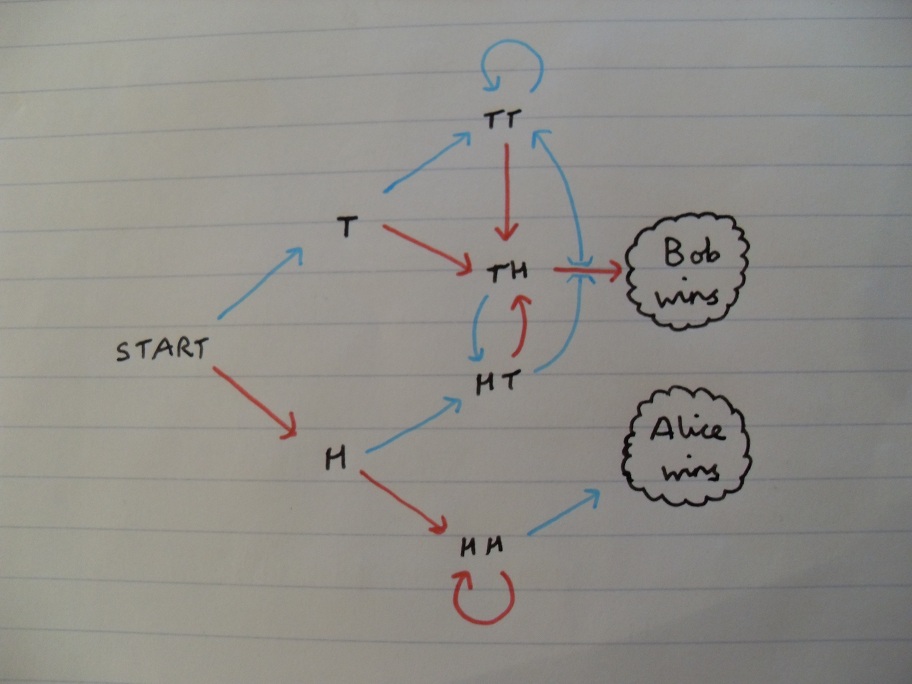

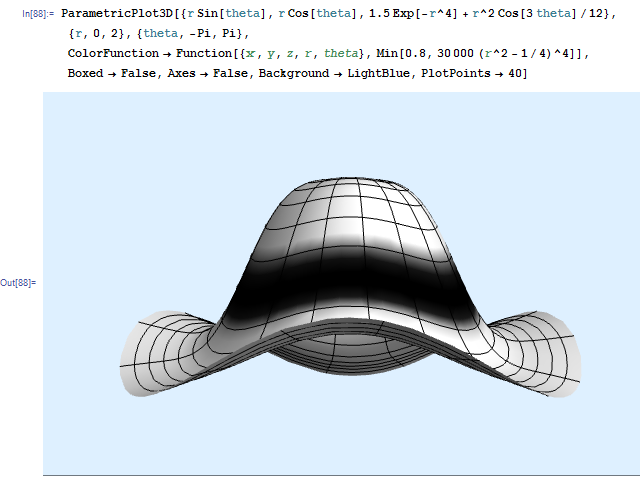

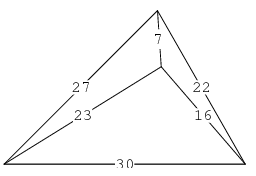

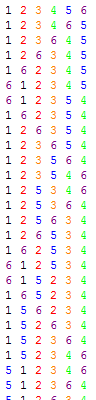

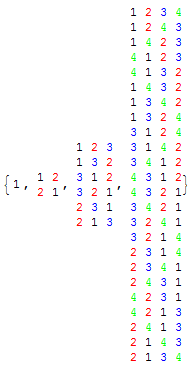

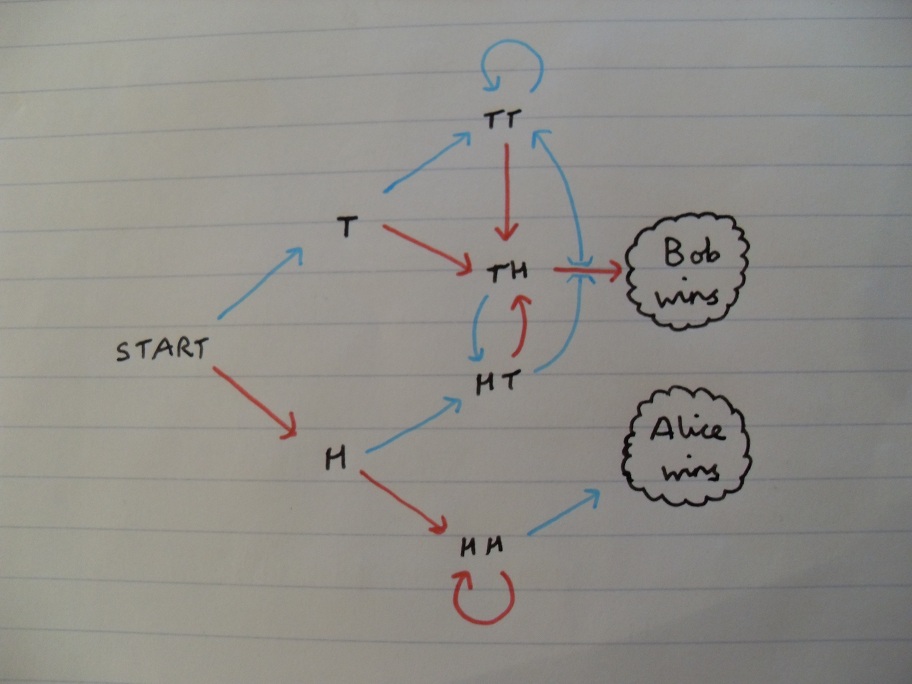

So, what are the probabilities of each player winning? We can analyse this by something called a Markov chain. We only need to keep track of the current symbol and the previous two, so the analysis is quite straightforward. In the diagram below, a red edge corresponds to a head appearing, and vice-versa.

We can think of these as being pipes transferring liquid between various containers, where half of the liquid in each container moves down the red arrow, and the other half propagates along the blue arrow. This diagram is rather simple, since it splits into two non-interacting halves, one of which leads to Bob almost surely winning, and likewise for Alice. It is evident from the diagram that Bob wins 75% of games played.

It turns out that the game is non-transitive, and Bob can always guarantee at least a 66% success probability, irrespective of Alice’s initial choice.

Markov music

It is similarly possible to replace the letters with musical notes, and weight the probabilities according to how often a particular note follows another note in a piece of music. Then, by following the Markov chain randomly, we can create something that locally resembles the original piece of music.

There is a reason I embolded the word ‘locally’. Even though we have all the right intervals (a technical term for two adjacent notes and the space between them), they’re not necessarily in the right order! The resulting tune, although it could hypothetically be identical to the original music, is most probably an awful cacophany. Richard Freeland wrote a computer program to do precisely this, and these were indeed his findings. For a piece of music to be pleasing, it needs to have some global structure.

We can, however, refine the original technique by using a larger ‘memory’ than a single note (for example, an entire bar). This would make a brief sample of (say) three seconds of the random tune appear indistinguishable from the actual music. The larger the memory, the better the tune.

Underwater basket-weaving

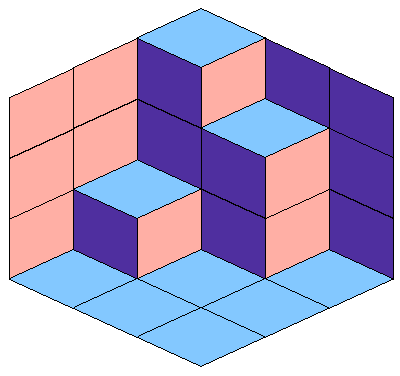

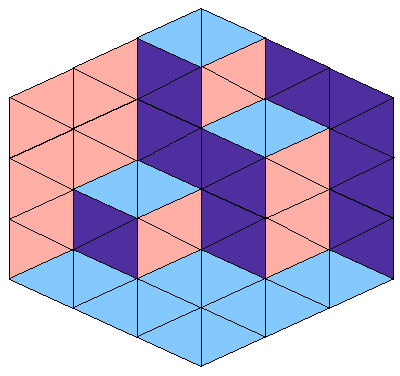

In the same way a musician can read a score of music and produce a tune, the 200-year-old Jacquard loom reads punched cards detailing instructions to weave complex patterns. As for whether it could perform the somewhat Herculean labour of underwater basket-weaving remains to be seen. Nevertheless, we could generate the punched card by a Markov process so as to create a randomised basket.

To keep this firmly within the realms of mathematics, here is a woven basket in the shape of a dodecahedron.