For this post, I’ve decided to do something different. Instead of the usual mathematical monologue, this is a more of a hands-on activity. It is centred around the golden rhombus, which is so named because the ratio of the diagonals is equal to phi. To construct the various examples and projects of your own, you will require the following materials:

- A4 card, on which to print off a plethora of golden rhombi. You can download both blue and green templates, each of which has 24 identical golden rhombi.

- Sellotape, as an adhesive.

- Scissors to cut out the golden rhombi from the A4 card.

- Plenty of patience, by which I mean the desirable personality trait rather than the solitaire card game.

Project 1: Rhombic triacontahedron

As implied by the name, the rhombic triacontahedron will require 30 rhombi to construct. Start off by placing the acute vertices of five of these rhombi together and Sellotape the edges together. This should form a basic three-dimensional star. Placing another five rhombi in the depressions of this star will give a decagonal dome:

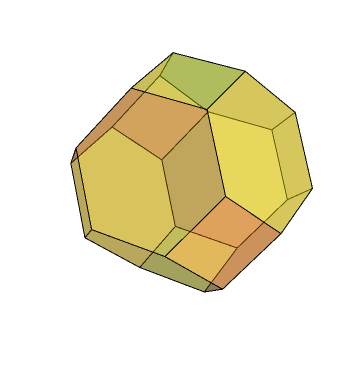

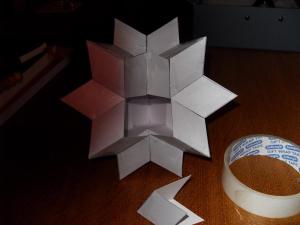

Continue extending this dome in the natural way, ensuring that three obtuse angles meet at alternate vertices and five acute angles meet at the other vertices. The completed rhombic triacontahedron should resemble a dome from every angle:

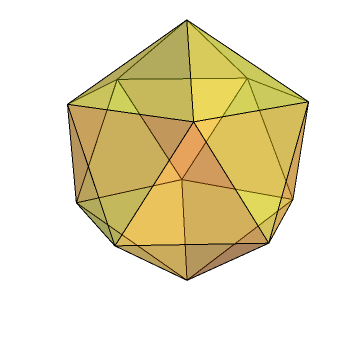

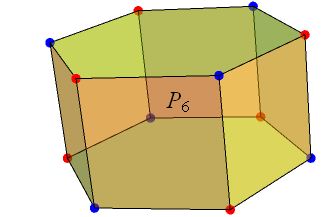

At the penultimate stage, it should look resemble the photograph above. You can then complete your rhombic triacontahedron by attaching the thirtieth and final rhombus. The rhombic triacontahedron (daltlP6) is the dual of the icosidodecahedron, one of the Archimedean solids. You can view the icosidodecahedron and many others in my interactive Wythoffian polyhedron builder.

Project 2: Rhombic hexecontahedron

The rhombic hexecontahedron is twice as expensive as the previous project. You may recognise it as the logo of the computational knowledge engine Wolfram Alpha. It seems that the best way to construct it is to begin with twenty ‘spikes’ of three rhombi each:

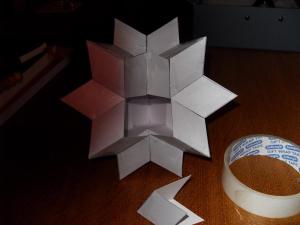

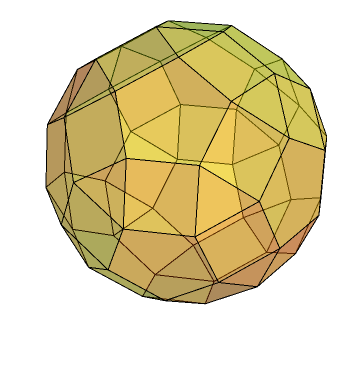

Assemble these in the same way you would build an icosahedron out of triangles. Be careful that there are five spikes around each of the innermost vertices. An almost-completed rhombic hexecontahedron is shown below:

As with the previous project, the last component is the most difficult one to attach. It might be best to pre-prepare the spike with Sellotape before adjoining it to the hexecontahedron. Then again, it is probably safest to just apply the tape incrementally, since otherwise yor hexecontahedron may meet a sticky end…

Projects 1 and 2 are compatible. Twelve rhombic triacontahedra can fit comfortably in the depressions of the rhombic hexecontahedron. You could produce a three-dimensional snowflake by further attaching a rhombic hexecontahedron to the end of each of the resulting bulges. I have neither the resources nor the patience to persue this, but I urge you to persuade a team of people to do it.

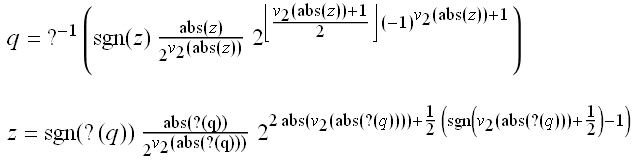

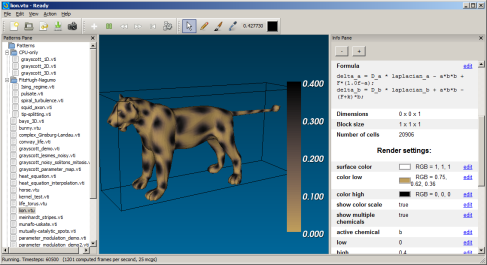

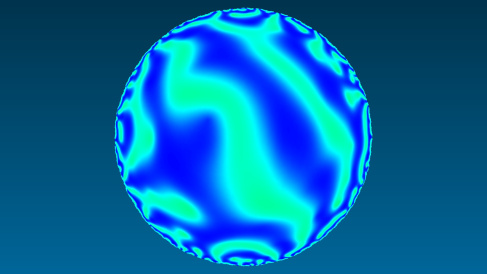

Project 3: Quasicrystals

With six rhombi, it is possible to make either of two ‘golden parallelepipeds’. The prolate version can be made by affixing two of the ‘spikes’ you made when building the rhombic hexecontahedron. Similarly, the oblate version is composed of two shallow hexagons, each of which comprises three rhombi. Assembly instructions aren’t really necessary for these simple solids.

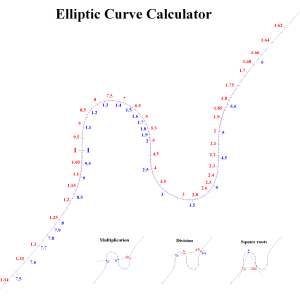

They’re really versatile. We can build a more rigid rhombic hexecontahedra out of twenty prolate parallelepipeds, or a rhombic triacontahedron using ten of each. This page explains how to construct the latter. These structures are prevalent in three-dimensional icosahedral quasicrystals of aluminium-lithium-copper. The mathematical model, the Ammann-Kramer tiling, is a three-dimensional analogue of the Penrose tiling. Indeed, my initial idea of making these rhombic polyhedra out of card was to explore the Ammann-Kramer tiling.

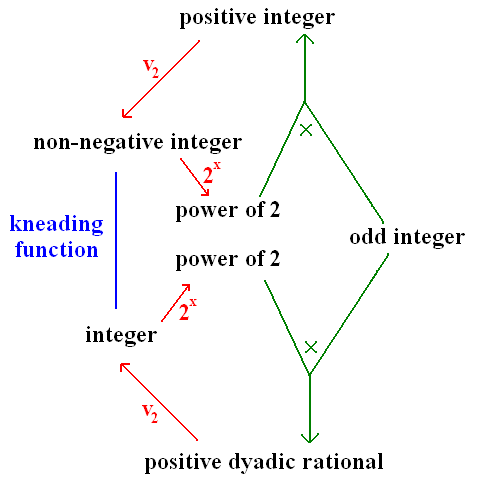

Project 4: Wieringa roofs

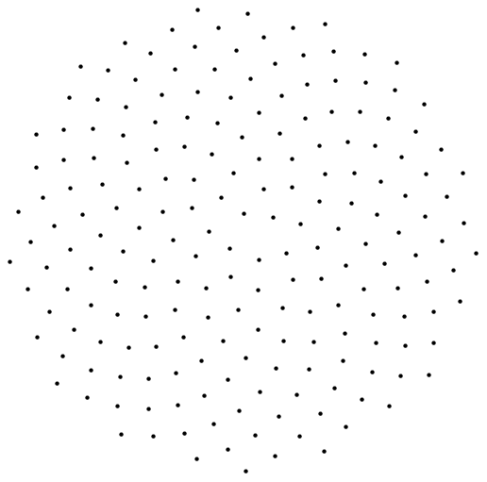

A Wieringa roof is a Penrose tiling with raised vertices, such that all of the rhombi are congruent. You can explore and rotate them in my other demonstration. The obvious method is to construct these things tile-by-tile with Sellotape. This is okay if you have a template to work with, such as my demonstration. You can quite easily get carried away adding extra rhombi; I managed to exercise constraint and limit myself to the following:

Actually, as you can see, I ran out of green rhombi. There are twenty-four rhombi on each sheet, whereas I needed twenty-five for the depth-3 iteration of the Wieringa roof. You may notice overlapping decagons in the image. There are two types, namely the ‘sun’ in the middle and the five (well, four complete ones) flanking it. As Petra Gummelt discovered, we can construct a Penrose tiling by overlapping these decagons. Unlike in the Sellotape method, you won’t have to restart if you make a mistake; you can simply rearrange the decagons.

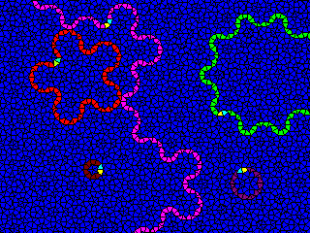

Project 5: Reptiles

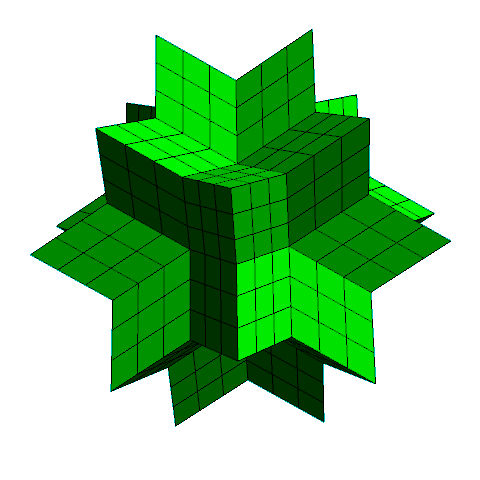

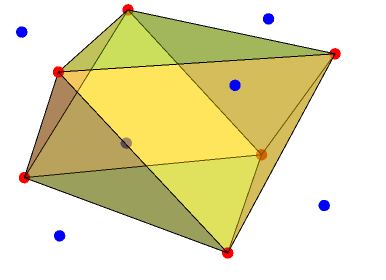

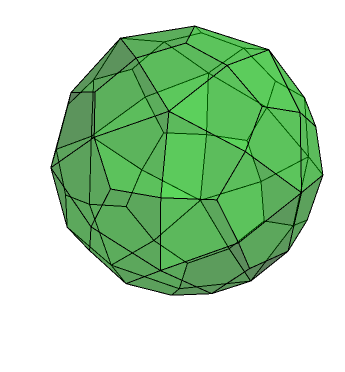

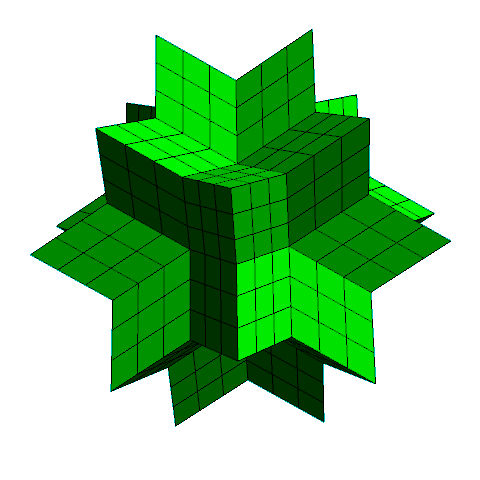

This word usually refers to a certain class of chordates such as turtles and snakes, but here is actually a portmanteau of ‘replicating’ and ’tiles’. The parallelepipeds are ‘unit cells’ which can be made into larger similar parallelepipeds if you have n³ of them. Hence, anything we make using parallelepipeds (such as the rhombic hexecontahedron) can be made in larger sizes. Rather than include an actual cardboard model, I’ve returned to my lazy ways and used Mathematica to generate one:

Like many reptiles, it is a pleasant shade of moss-green. Of course, taking the reptile analogy too literally, you could conceivably create a crocodile from the ‘spikes’ used in the construction of the rhombic hexecontahedron.

Be creative

Rather than merely adhere to the blue and green templates I have included, you could print them out on the reverse of some lovely metallic silver card from Paper Chase (unlike the BBC, there are no issues with product placement on Complex Projective 4-Space). Don’t refrain from decorating your rhombi with sequins; to further incorporate the golden ratio, you could use Fibonacci sequins!

Please send in photographs of your constructions. Only provide copies, as we are not able to return originals. If you send in enough of your creations, I should be able to compile a video of them to the tune of Left Bank Two (thanks go to Tom Rychlik for wasting many hours of his life trawling through YouTube comments to ascertain the name of the tune, as he revealed whilst we were eating Crispy Creme doughnuts — the simply connected British variety, not those toroidal American doughnuts). Please include your forename so that we can attribute your artwork to you.