Here’s the post I promised you a while ago. I wrote the first part of this in an e-mail on Burns’ Night of 2011, and the main idea (which Alex Bellos termed the ‘Goucherian calendar’) was mentioned in the Guardian. The rest of this post uses more advanced mathematics to determine lunisolar and eclipse cycles.

Calendars and continued fractions

In 45 BC, Julius Caesar reformed the Roman calendar to closely adhere to the tropical year. The Julian calendar has a leap year every four years, and thus has an average year length of 1461/4 = 365.25 days. This is not a particularly accurate approximation to the actual tropical year of 365.2421897 days, so Pope Gregory later commissioned an updated version, namely the Gregorian calendar we use today. It has a rather complicated system of rules, specifically:

- If 400|N, then year N is a leap year, otherwise;

- If 100|N, then year N is a regular year, otherwise;

- If 4|N, then year N is a leap year, otherwise;

- Year N is a regular year of 365 days.

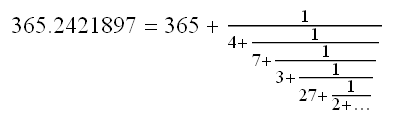

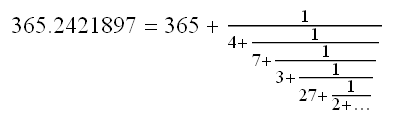

It is not too difficult to calculate that the mean length of the year is 146097/400 = 365.2425 days. Whilst much closer to the actual figure than the Julian calendar, it is far from perfect, and pretty inefficient. What we desire is a best rational approximation to the number 365.2421897. One way to do this is to find 365.2421897 on the Ford circles, and draw a vertical line to see which circles it intersects. There is a numerical alternative, which involves computing the continued fraction of 365.2421897.

The number 27 is quite large, so the term 1/(27+1/(2+…)) is reasonably small. If we ignore it and truncate at this point, we obtain the approximation 365+1/(4+1/(7+1/3)) = 365.2421875. This is about 140 times closer than the approximation given by the Gregorian calendar. As a mixed fraction, this is 365+31/128. Hence, we can construct a 128-year cycle, which is far more efficient than the 400-year Gregorian calendar.

- If 128|N, then year N is a regular year, otherwise;

- If 4|N, then year N is a leap year, otherwise;

- Year N is a regular year.

See? Much simpler. The next discrepancy between my calendar and the Gregorian calendar occurs in the year 2048, which is a leap year in the Gregorian calendar but not in mine.

We have established that best rational approximations make good calendars. What if a sadistic deity wanted to create a solar system to make it intentionally difficult for the inhabitants to design an accurate calendar? Obviously, we would want a number that has poor rational approximations. The basis is again continued fractions, but a value of phi = 1.618033… would be optimal for this purpose. It has a continued fraction of [1; 1, 1, 1, 1, …], with the best rational approximations equal to ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers. In some sense, it is the ‘least rational’ number.

Let’s presume we had a mean tropical year of 365.618033… days. When should we have leap years to adhere as closely as possible to the changing seasons? A periodic calendar would be no good for this, so we instead resort to an aperiodic calendar! The optimal solution is given by the golden string:

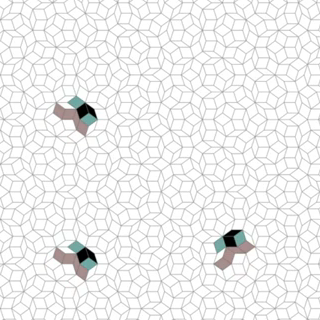

L R L L R L R L L R L L R L R L L R L R …

We can create this sequence by using a Lindenmayer system, or L-system. When given as instructions to a robot for drawing a line, L-systems lead to beautiful fractal curves. A famous example of a curve generated in this way is the Koch snowflake. The paths traced out by my glider on the kite-and-dart Penrose tiling also have structures determined by L-systems. The golden string itself can be found in Penrose tilings and can be considered to be a one-dimensional quasicrystal.

Lunisolar calendars and the LLL algorithm

If we want to find a simple integer relationship between two quantities, we can use continued fractions. Let’s try this again on the tropical year (365.2421897 days) and the synodic month (29.530589 days). The ratio is 12.368266, which has the continued fraction:

[12; 2, 1, 2, 1, 1, 17, 3, 12, …]

Ooh! 17 is a nice, big number! Let’s truncate before that. This gives us [12; 2, 1, 2, 1, 1], or 235/19. So, 235 synodic months is almost exactly 19 tropical years. This is known as the Metonic cycle and features in the Hebrew calendar. However, what if we want to find an integer relation between not two, but three or more quantities? How do we discover an integer relationship between the length of a day, synodic month and tropical year?

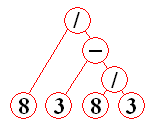

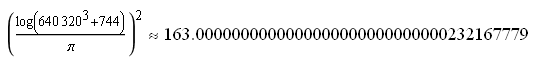

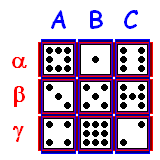

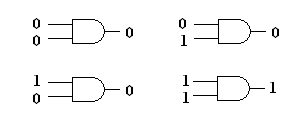

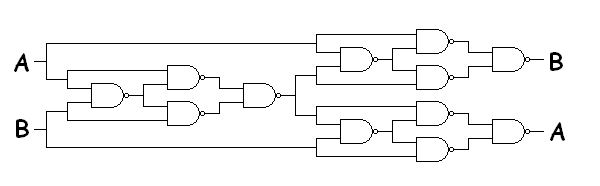

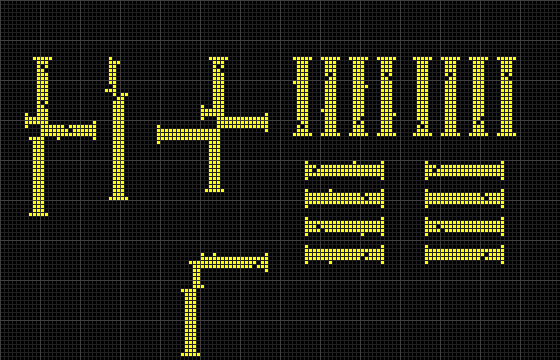

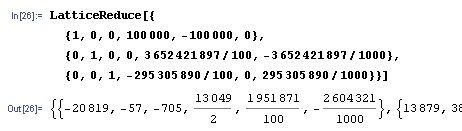

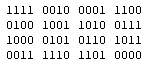

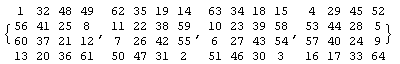

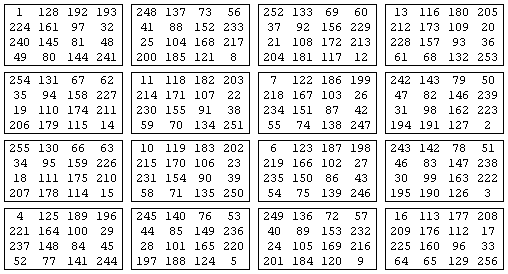

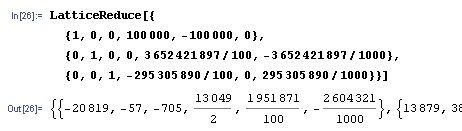

The answer is to use the LLL (or Lenstra-Lenstra-Lovasz) algorithm. I imagine that the Lenstrae in the title were two distinct (probably related) mathematicians, and not an indication that Lenstra deserves twice as much credit as Lovasz for inventing the algorithm. It’s not really important how it works, just that it does. It’s actually designed for simplifying a basis for a n-dimensional lattice, but we can use it to solve our problem as well. I gave Mathematica the following input, producing this output:

I’ve cropped the output, as only the first vector is important. What I’ve essentially told the LLL algorithm to do is to find integers x, y and z, such that:

- x is small;

- y is small;

- z is small;

- x days is approximately z synodic months;

- x days is approximately y tropical years;

- y tropical years is approximately z synodic months.

The first vector informs us that one solution is 20819 days = 57 tropical years = 705 synodic months. This is a really good approximation; it’s only 5 minutes away from the actual tropical year, and is better than the Julian calendar. Moreover, 57:705 is the ratio 19:235 of the Metonic cycle.

Saros and Exeligmos

Patterns of solar and lunar eclipses are not really related to the spin of the Earth on its axis, or even the absolute rotation of the Earth around the Sun. More importantly, it is the relationship between the synodic month and draconic month (27.212221 days). We can use continued fractions to find a good rational approximation to 29.530589/27.212221. A reasonably good rational approximation is 242/223, which gives a cycle known as Saros. Every Saros, a similar eclipse is repeated.

If we want to find a cycle where eclipses occur at a similar time of day, then we’ll have to incorporate the length of one day into the calculation as well. Let’s use the LLL algorithm again, but replace 365.2421897 (the year, which is unimportant) with 27.212221.

We see that 19756 days, 726 draconic months and 669 synodic months all approximately equal each other. This menage a trois is known as the Exeligmos. The observant amongst you may notice that it is equal to precisely three Sarosses. (I actually had to alter the Wikipedia page, which incorrectly stated that the Exeligmos is 725 draconic months.) Every Exeligmos, a similar eclipse occurs at a similar time of day.

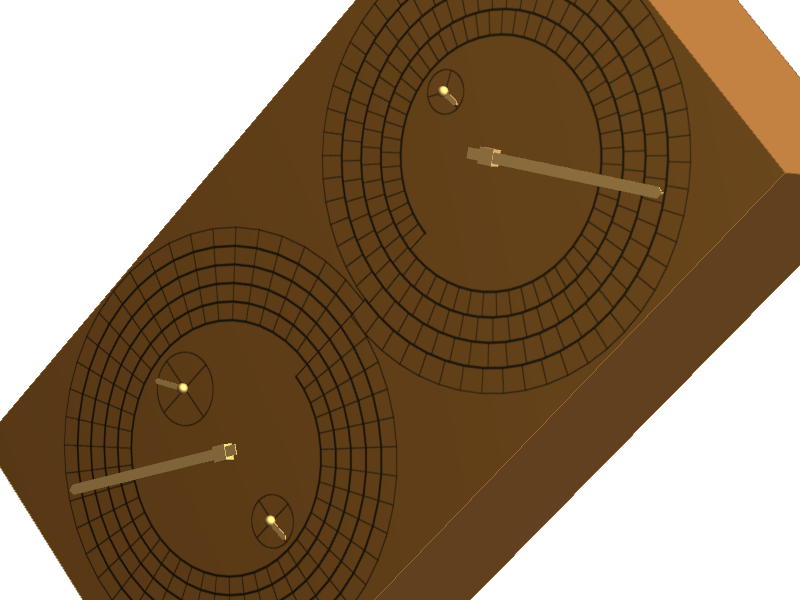

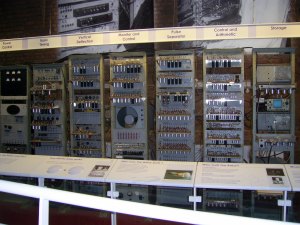

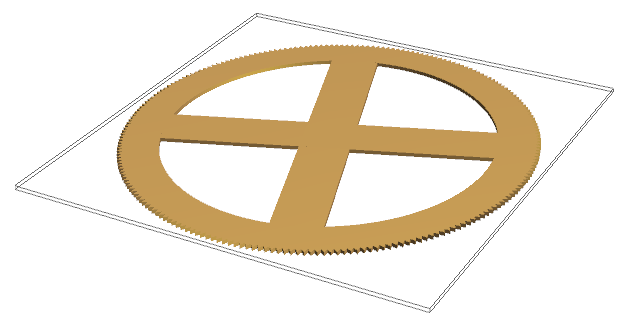

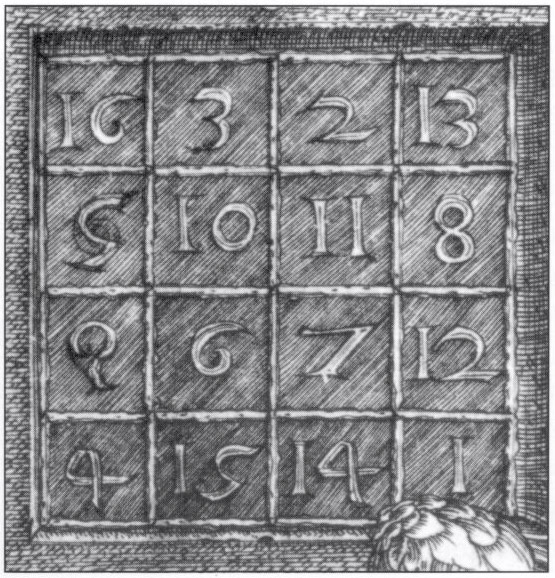

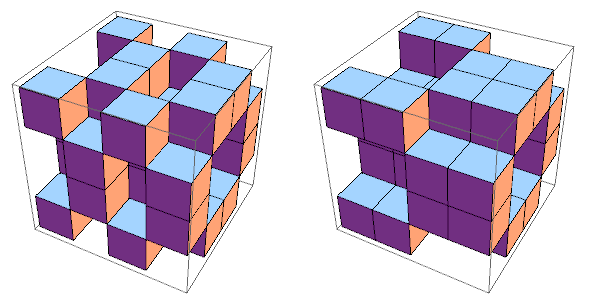

Why bother doing all of this? The answer is to build automata for predicting eclipses. On Syracuse, an island in Ancient Greece once inhabited by Archimedes, the legendary Antikythera mechanism was constructed. This is a complex system of gears, each with an integer number of teeth, and combines a lunisolar calendar with a planetary orrery. The Antikythera mechanism incorporates the Saros, Exeligmos and Metonic cycles amongst others, and is really impressive. This mechanical sophistication was never replicated until the Renaissance, when mechanical clocks were developed.

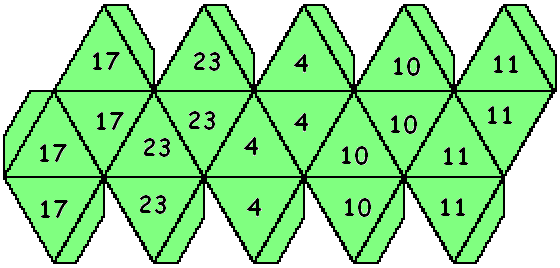

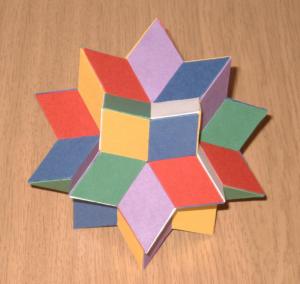

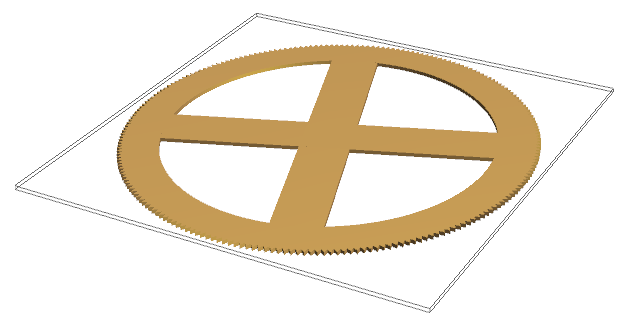

I’m intending to create a simulation of the Antikythera mechanism to include on the Wolfram Demonstrations Project. Shown above is the largest, 224-toothed gear, which revolves for every simulated year. One gear down, 29 to go…